Mapping Urban Safety and Security: An Intersectional Approach in Umeå, Sweden

This thesis investigates how safety in public space can be more comprehensively understood by integrating established urban safety design principles with situated, qualitative insights. As a theoretical background, my thesis draws on various lens of urban safety studies, which gained prominence in the 1960s with the growing recognition that urban planning is never a neutral practice. The spatial configuration of cities shapes behavior and can influence the occurrence of crime, leading to the development of certain design principles as key components of crime-prevention strategies. Feminist urbanism later broadened this perspective by demonstrating that the built environment not only affects crime patterns but also shapes people’s perceptions of safety and their freedom of movement. This shift highlighted the importance of safety perception as an essential dimension of urban safety research and encouraged the integration of qualitative and participatory methods into planning processes. However, despite their analytical value, these approaches are often simplified or omitted in practice due to time and resource constraints.

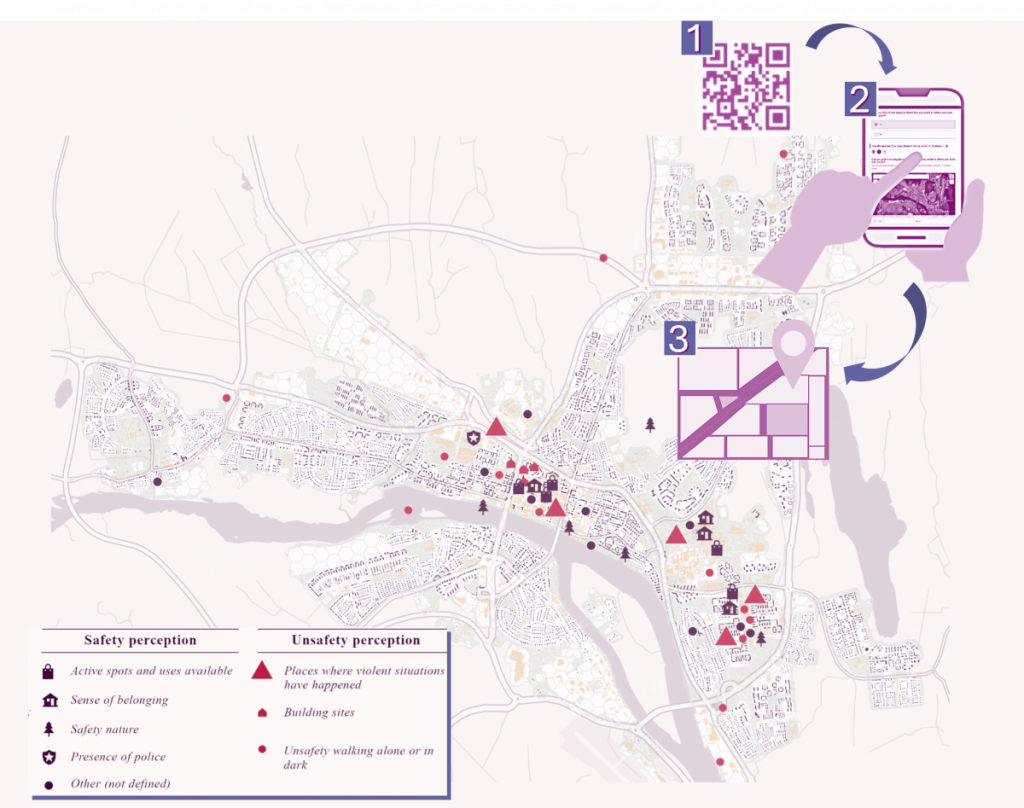

The study adopts a dual methodological approach to examine safety in Umeå, Sweden. On the one hand, it consists of a quantitative analysis based on existing design guidelines for safe and inclusive urban environments. On the other hand, it involves a qualitative analysis derived from a digital survey that allowed participants to identify safe and unsafe locations and describe their experiences. Together, these approaches aim to illuminate the value of participatory methods and qualitative data in generating insights that purely quantitative techniques or material design interventions could overlook.

The quantitative analysis was structured through a matrix of twelve indicators developed from feminist and intersectional design guidelines. These indicators were grouped into five thematic categories: mobility, public spaces, safety perception, facilities and urban morphology. They included factors such as mixed land uses, pedestrian connectivity, lighting conditions, visual openness or street proportions. Data were collected from municipal sources, public databases and field observations, and analyzed using ArcGIS Pro. Analytical maps were generated for each indicator and synthesized through spatial statistics. The accompanying survey produced a smaller dataset (due to time constraints) and GDPR constraints limited the collection of personal or sensitive information, yet it yielded valuable insights beyond the scope of GIS analysis.

The findings reveal several notable patterns. In suburban residential areas with detached houses (commonly perceived as safe) GIS indicators exposed deficiencies relative to the design guidelines, including limited land-use diversity, a lack of community spaces and constrained mobility options (high dependance on private transport). Survey responses echoed these issues, highlighting restricted social interaction and concerns about traffic. Furthermore, the survey underscored climatic and temporal dimensions, largely absent from the GIS analysis. Umeå’s long, dark winters and resulting snow accumulation can significantly reduce safety perception and restrict mobility, particularly near homes, affecting certain groups disproportionately. These context-specific challenges would have remained obscured without residents’ situated knowledge, since the design guidelines used to develop the GIS indicators paid little attention to climatic and temporal specificities. Historical memory also emerged from survey responses as a key factor shaping perceptions: references to the Hagamannen case illustrated how past events continue to influence feelings of unsafety decades later, but only for those aware of Umeå’s past.

Overall, the study demonstrates that quantitative and qualitative approaches are mutually indispensable. GIS enables broad, systematic spatial analysis, but lacks the contextual grounding that only residents can provide. Even limited participatory data can enrich, or even challenge, design guideline-based assessments. The research underscores the need for intersectional analyses capable of identifying who is most affected by standardized design solutions, particularly against the backdrop of political narratives that increasingly rely on surveillance and exclusion.

Looking forward, urban safety research and policy must pay closer attention to local conditions, such as climate, community histories and everyday experiences, while avoiding universal assumptions about what constitutes a safe environment. Critical scholarship is increasingly questioning the simplistic safe/unsafe binary and emphasizing the complexity of urban life, including the importance of acknowledging negative emotions as part of everyday experience. A key dimension still underexplored in urban safety studies is the domestic scale. Safety in public space cannot be fully understood without considering safety at home, especially given long-standing critiques of the public/private divide.

Crime plays an important role in shaping how safe we feel in our environments, but so do the social, cultural, political and economic codes that produce our ideals, shape our emotions and guide our behavior. And these dynamics become accessible through local and situated knowledge.

The quantitative analysis was structured through a matrix of twelve indicators developed from feminist and intersectional design guidelines. These indicators were grouped into five thematic categories: mobility, public spaces, safety perception, facilities and urban morphology. They included factors such as mixed land uses, pedestrian connectivity, lighting conditions, visual openness or street proportions. Data were collected from municipal sources, public databases and field observations, and analyzed using ArcGIS Pro. Analytical maps were generated for each indicator and synthesized through spatial statistics. The accompanying survey produced a smaller dataset (due to time constraints) and GDPR constraints limited the collection of personal or sensitive information, yet it yielded valuable insights beyond the scope of GIS analysis.

The findings reveal several notable patterns. In suburban residential areas with detached houses (commonly perceived as safe) GIS indicators exposed deficiencies relative to the design guidelines, including limited land-use diversity, a lack of community spaces and constrained mobility options (high dependance on private transport). Survey responses echoed these issues, highlighting restricted social interaction and concerns about traffic. Furthermore, the survey underscored climatic and temporal dimensions, largely absent from the GIS analysis. Umeå’s long, dark winters and resulting snow accumulation can significantly reduce safety perception and restrict mobility, particularly near homes, affecting certain groups disproportionately. These context-specific challenges would have remained obscured without residents’ situated knowledge, since the design guidelines used to develop the GIS indicators paid little attention to climatic and temporal specificities. Historical memory also emerged from survey responses as a key factor shaping perceptions: references to the Hagamannen case illustrated how past events continue to influence feelings of unsafety decades later, but only for those aware of Umeå’s past.

Overall, the study demonstrates that quantitative and qualitative approaches are mutually indispensable. GIS enables broad, systematic spatial analysis, but lacks the contextual grounding that only residents can provide. Even limited participatory data can enrich, or even challenge, design guideline-based assessments. The research underscores the need for intersectional analyses capable of identifying who is most affected by standardized design solutions, particularly against the backdrop of political narratives that increasingly rely on surveillance and exclusion.

Looking forward, urban safety research and policy must pay closer attention to local conditions, such as climate, community histories and everyday experiences, while avoiding universal assumptions about what constitutes a safe environment. Critical scholarship is increasingly questioning the simplistic safe/unsafe binary and emphasizing the complexity of urban life, including the importance of acknowledging negative emotions as part of everyday experience. A key dimension still underexplored in urban safety studies is the domestic scale. Safety in public space cannot be fully understood without considering safety at home, especially given long-standing critiques of the public/private divide.

Crime plays an important role in shaping how safe we feel in our environments, but so do the social, cultural, political and economic codes that produce our ideals, shape our emotions and guide our behavior. And these dynamics become accessible through local and situated knowledge.

Read the full thesis HERE.

Lisa Hillerbrand Martín är arkitekt utbildad i Spanien med fokus på bioklimatisk design och hållbarhet. Efter flera års arbete flyttade hon till Sverige för att fördjupa sig i GIS. Hon är nu doktorand i feministiska geografier vid Karlstads universitet, där hennes forskning rör geografías de violencia doméstica och hur sociala nätverk och urban miljö påverkar överlevares rörelsemönster och stödnätverk.