“Women and men not walking in the same paths”- Public space and public policy through intersectionality

"Women and men not walking in the same paths"- Public space and public policy through intersectionality

Contemporary public space is gendered. Women’s prevailing feelings in public space are fear, anxiety, and unsafety, as suggested by the literature. Urban planning, alone, cannot resolve the patriarchal system in which women are oppressed, restricted, and afraid of public space. Nevertheless, there are directions in which we can move to limit restrictions and shape public spaces that complement women’s needs.

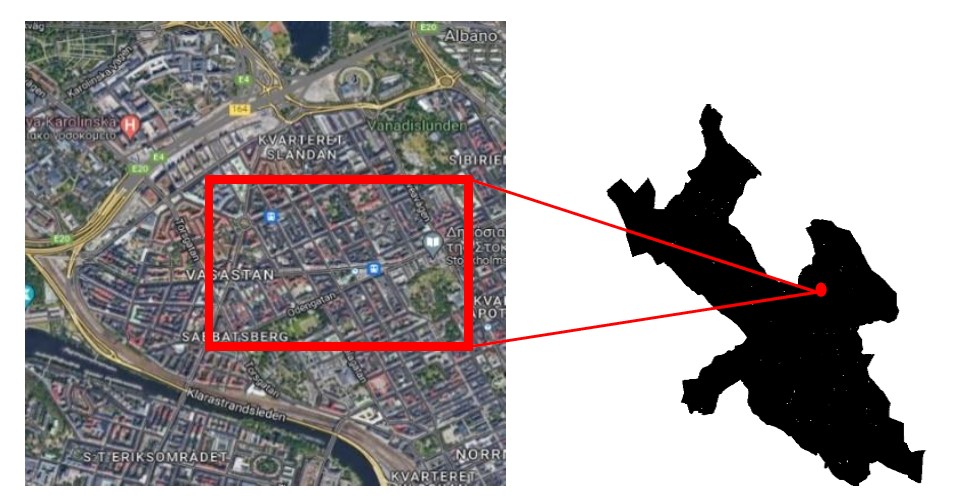

My interest in the female experience in the public space and the aim of elevating women’s voices led me to the creation of this study on “Women and men not walking in the same paths”- Public space and public policy through intersectionality. In this study, the lens through which women’s experience in public space is explored is intersectionality. The term was coined by Crenshaw (1989) to emphasize the interrelationship of race with other identities such as class, gender, ethnicity, etc. There are scholars that used this theory with a different focus. Key concepts for the study were public space and public policy. A central public space in the city of Stockholm was used as a tool for researching women’s experiences (Map 1).

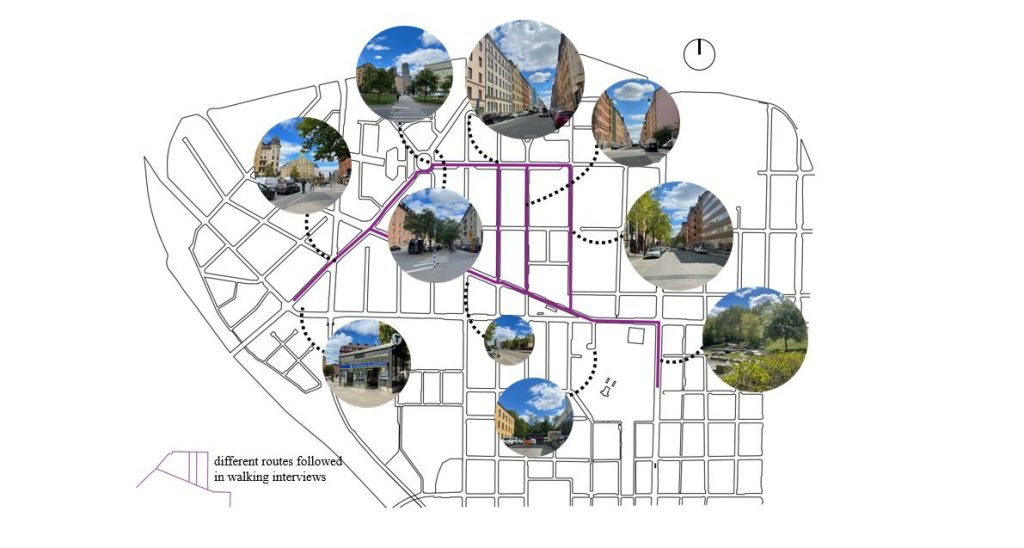

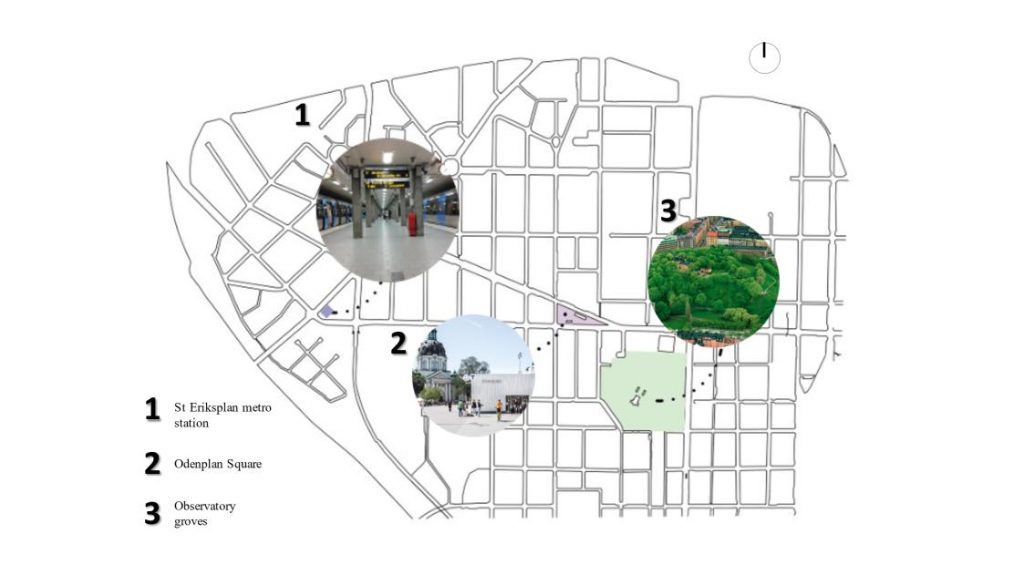

The methodology consisted of qualitative research. Using two methods, walking interviews in a central area of Stockholm and the story completion method. Thus, during the study, we walked with women participants in a central area of Stockholm (Map 2) and stopped at three public places (Map 3) where the women were given a story and they asked to finish it.

The findings were developed around three main themes 1. How women were introduced to public space 2. How women experience public space and 3. How women would like public space to be. Women discussed the feelings of fear, anxiety, and vulnerability they feel in the public space intertwined with the restrictive way it was introduced to them and in conjunction with the different identities they carry. They referred to the simple things they would do if the public space were open and non-patriarchal like taking a walk at night or walking while listening to music.

An important part of this study was the reuse of knowledge gained from empirical work with the aim of using intersectionality in public policy and planning. Thus, the following four recommendations were formed:

- Integrate intersectionality into planning education.

- Policymakers to connect more and literally with the human individual experience.

- Participatory planning using diverse methods.

- People on the margins, and their multiple identities, should be the center of the planning process and policymaking.

Women’s experience in contemporary public space emerges from a disadvantageous position. It needs to be further explored, by delving into women’s narratives and further enhancing planning and policy practices to the direction of women to be the main part of the process. Drawing from that anticipated challenge of women’s narratives set planners and policymakers, should further explore women’s experience in public space but through intersectional analytical lenses.

Reference:

Crenshaw, K., 1989. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, pp. 139-167.

Ioanna Petridou

Urban planner and human geographer from Greece. I am very interested in investigating the relationship between women and public space and aspire to be a part of the research in order to design public spaces that make women feel safe and liberated.